HER WILDFLOWER GARDENS AT ONE HUNDRED FIVE ORCHARD

speculative drawing

As printed in Drawing Futures, The Bartlett, UCL, page 129.

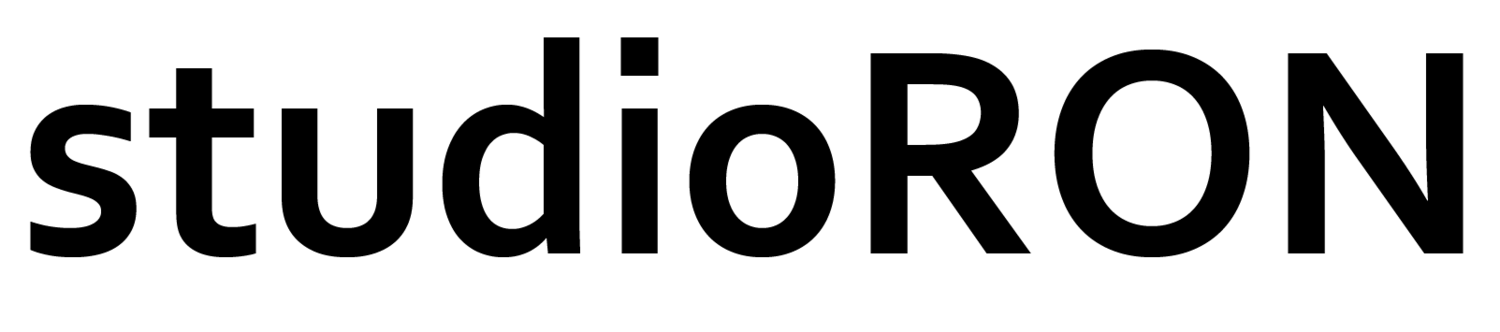

‘Her Wildflower Gardens at One Hundred Five Orchard’ employs physical analogue drafting methods as a means to develop a set of drawings that explore nostalgia as a significant driver of architecture through the physical assembly of drawings. The drawings explore a methodology that describes the processes of nostalgia-developed architectures within the obscure boundaries between the casual gardener in their small home plot and the present mechanistic state of commercial agriculture. Here, nostalgia is to be defined as the longing for or recollection of a previous image of a place when faced with its current, changed, physical state.

The now-defunct eighteenth-century Dolton Farm in Feasterville, Pennsylvania acts as a site for investigating nostalgia as an architectural driver in two significant ways. First, the former farm is a site with some intact structural remains, allowing new architectures to be physically situated within an existing context and informed by existing materials. Second, the site provides a historic programme that can be recalled and redeployed on a new scale. On the site of a once-historic rural farm is a new automated garden in what is now a suburban residence. The subtle shift in the scale and purpose of the land’s farming programme explores how expectations and reality can diverge, which triggers sensations of nostalgia.

The drawings exploit historically-based expectations of farming and personal responses to idealised images of manual labour in the vast fields of early twentieth-century farming. These images are pitted against the mechanistic nature of modern computerised farming equipment. This mechanisation of a once-massive human effort is translated to the physically laborious yet recreational pursuit of gardening.

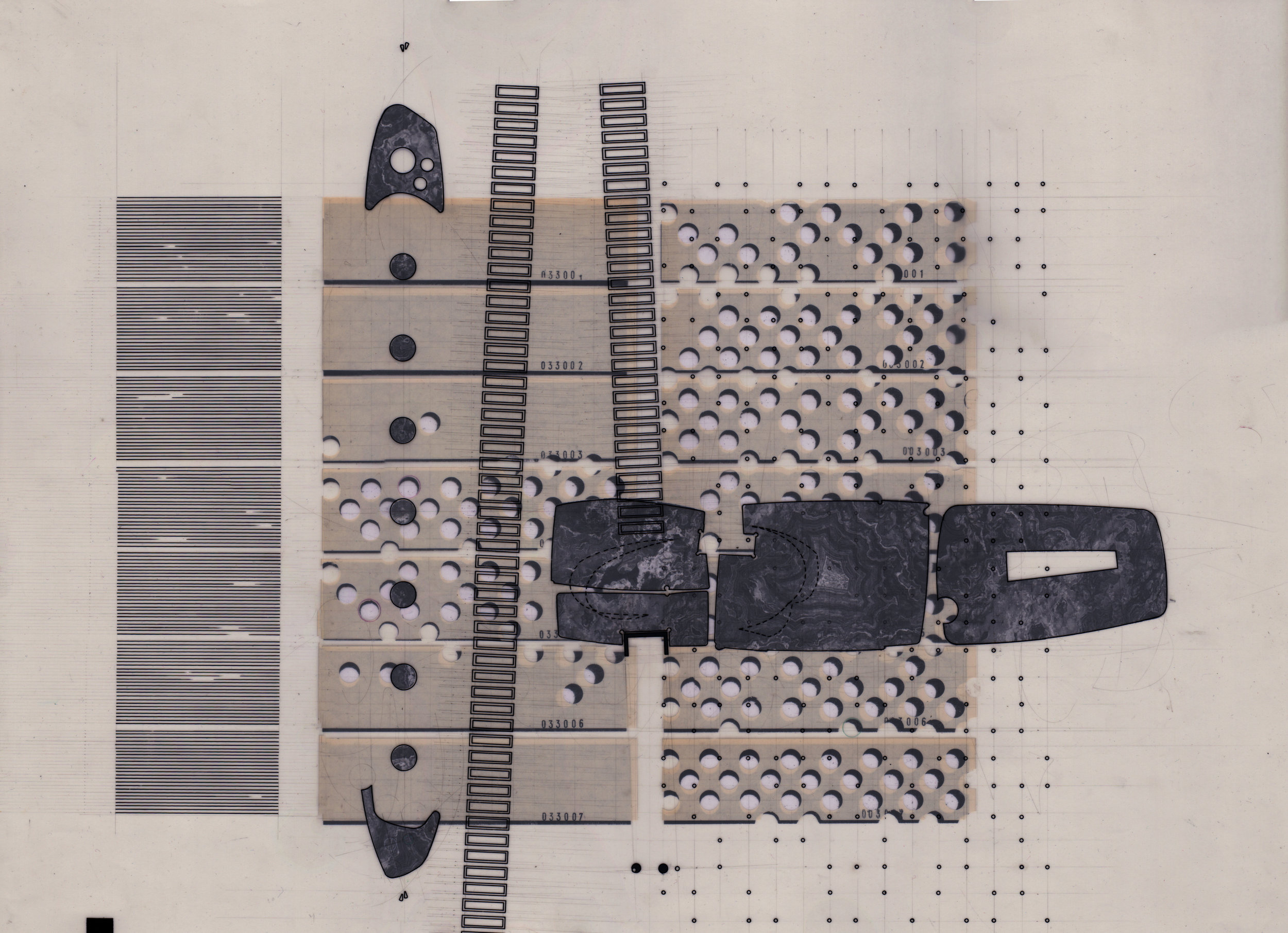

The production methods for the drawings provide a manual means to describe an automated system. Ink, pencil, tape and collaged imagery on and between sheets of vellum and Dura-Lar allow for multiple formal, material and sub-programmatic propositions to be overlaid, combined and challenged. Their simultaneous inclusion among the multiple physical drawing layers gives each proposition its own space to dawdle within the historic timeline and project new definitions of place onto the site.

Constructed at the same time is a model developed within shallow drawers. Divided by the drawers’ boundaries and partitions, existing site topography and labelled landscape artefacts are organised according to seasonal plantings. The drawings and the model feed off one another as moments of the models are collaged into the drawings and moments of the drawings force the reorganisation of the model. Moments of the model’s reorganisation are captured within the drawings to act as a record of the garden’s movement. This action physically captures and redisplays a moment in time when the garden differed from its existing state, thereby forcing the model and drawings to act according to the triggers of nostalgia.

The drawings also explore a series of new minor programmatic protocols that support the wildflower gardens and recall the garden’s historic use, including rabbit deterrence boundaries, duckboard boot-washing platforms and arborvitae view obstacles. The minor programmes are introduced to support the new automated wildflower garden. Beneath the larger programmatic headings, minor themes more personally related to the neighbourhood residents yet related to the site, such as neighbourhood hearsay, rumours and familial tall tales, are introduced to avoid complete autonomy or continuous circular referencing between the history of the farm and the new automated gardens.

Seven gardens of wildflowers are irrigated by collected rainwater from the storms of spring and early summer. Sub-surface expansion bladders are pressurised by six tidal pistons driven by the tidal inlet of the Delaware River and, in the event of piston failure, one hand pump. The collected rainwater is pumped through a series of irrigation corridors, which are infused with varieties of wildflower seeds, and deposited directly into a dimpled silt earth surface above. The gardener views her wildflowers from atop a copper patina filtration platform. The garden’s boundaries are ever-changing within the two-acre plot, as they expand and contract at the will of the tidal pistons compressing water into the irrigation lines. At the end of the season, she sets out a roaming chimney, turning the fields into charcoal to reload the filtration platforms and prepare the earth for another season.

Although scale is rigorously enforced during production of the drawings, the final products do not directly portray the garden’s relationship to the human body. The autonomy of the garden’s programmatic actions excuse the gardener from daily tending in order to attend to her new roles as both an intermittent system mechanic and an observer of the garden. The ambiguous sense of scale within the drawings frames the recall of images of vast fields once required by commercial farms. That image is positioned against the state of the wildflower garden, which is situated on a selected parcel fluctuating within the more recently established boundaries of residential property lines. This further undercuts expectations brought on by the site’s expanse when considering its history.

The physically developed drawings and model furthermore act as newly developed artefacts which track variations in the life of the wildflower gardens. Thus, the gap between initial contact and development of a memory of place and the return contact and recall of what the place once was is bridged. From this, one can develop an architecture from the processes of nostalgia.